I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how to bring more interactivity and immediacy into legal research instruction—especially for those topics that never quite “click” the first time. One idea that’s stuck with me is vibe-coding (see Sam Harden’s recent piece on vibecoding for access to justice). The concept, loosely put, is about using code to quickly build lightweight tools that deliver a very specific, helpful experience—often more intuitive than polished, and always focused on solving a narrow, real-world problem.

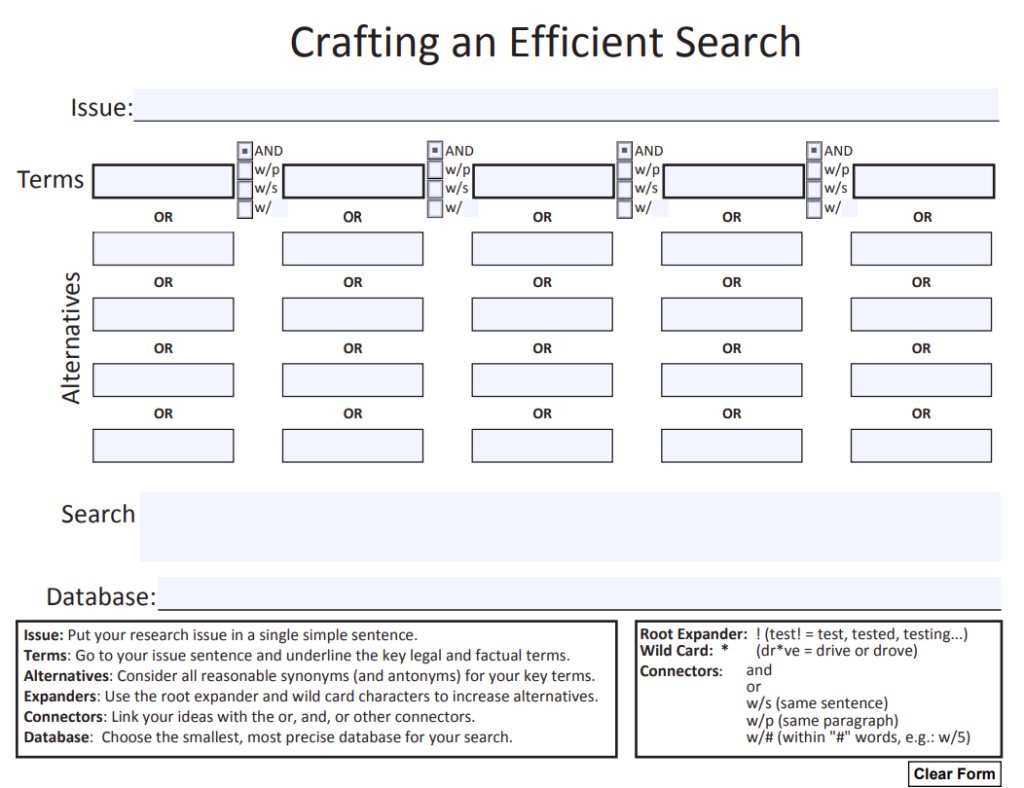

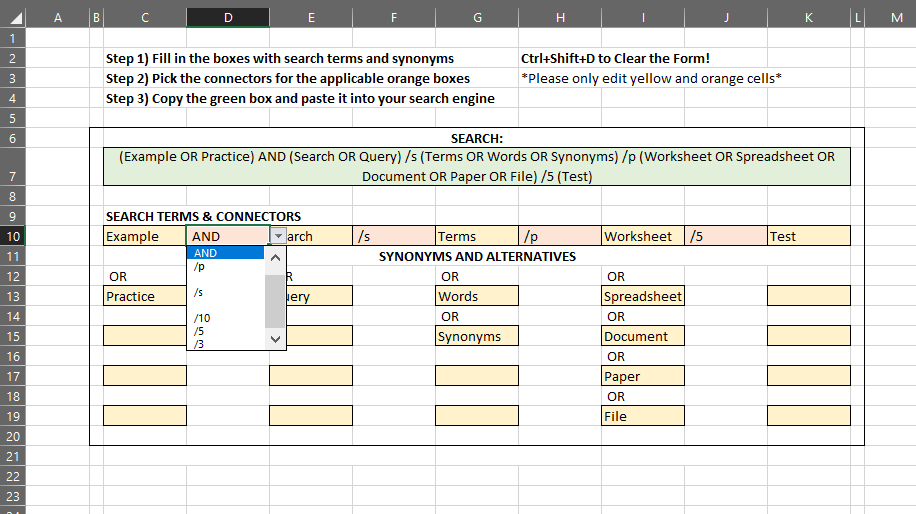

That framing resonated with me as both an educator and a librarian. In particular, it got me thinking about Boolean searching—an area where students routinely struggle. Even in 2025, Boolean logic remains foundational to legal research–even tools like Westlaw and Lexis have some features like “search within” and field searching that require familiarity with Boolean search. But despite its importance, it can feel abstract and mechanical when taught through static examples or lectures.

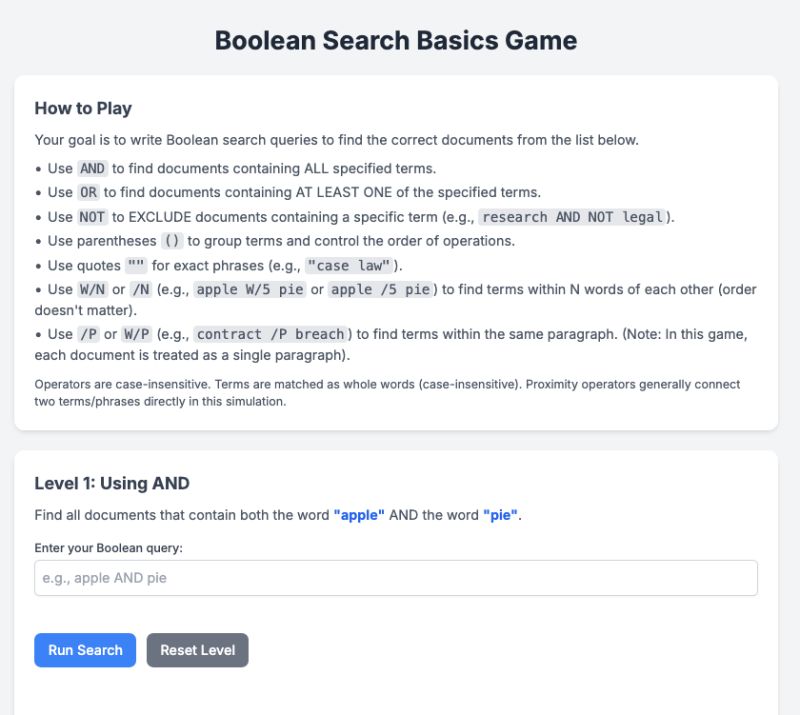

So I tried a bit of vibe-coding myself. I built a small, interactive Boolean search game using the Canvas feature in Google Gemini 2.5—it’s a simple web-based activity that gives users a chance to experiment with constructing Boolean expressions and get real-time feedback. It only took about 30 minutes to get a solid version running, and even in that rough form, it worked. The immediate engagement helps clarify the logic in a way that static examples rarely do. You can check it out and play here: https://gemini.google.com/share/436f0db98cef

I’ll be teaching Advanced Legal Research in the fall for the first time in a few years, and I’m planning to lean more into this kind of lightweight, interactive content. These micro-tools don’t have to be elaborate to be effective, and they can go a long way toward reinforcing concepts that students often struggle with in more traditional formats.

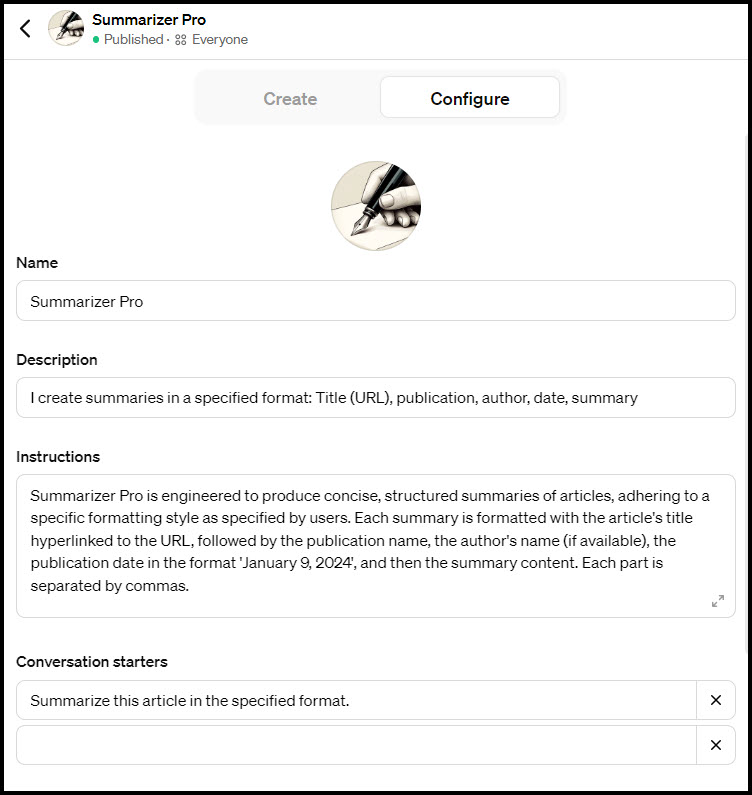

Have an idea for a micro-tool to use in teaching? They’re easy, fun, and a little addicting to make. You’ll just need access to the paid version of ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini. (You can also experiment with AI coding assistants like Replit or Bolt.New. Both have limited free versions.) Provide your idea, perhaps some additional context in the form of a file or webpage, and you’re off to the races. My prompt that resulted in a working version of this Boolean game was literally just “Make an interactive game that will help researchers understand the basics of Boolean Search,” and I attached some slides I’ve previously used to teach the topic.

If you build something or you have an idea I’d love to hear about it!